Brand purpose doesn’t build brand distinctiveness. Brand ideas do.

In a purpose-led world, it’s the how, not the why, that builds connected brands.

Embraced and ridiculed in equal measure, the notion of locating a ‘purpose’ (or a ‘why’) at the heart of a brand has become the de facto marketing trend of our age.

Devotees of Simon Sinek point to correlations between brand growth and brand purpose. Detractors point to an increasingly crowded space of interchangeable, irrelevant lofty visions that have lost their connection with the product they’re selling.

Is the whole notion flawed, or are we just using it wrong?

Defining brand purpose

Firstly, what’s the point of a purpose? Ostensibly, it’s to deliver a north star for a brand or business that not only aligns a company internally but invites those outside of it (the consumer) to be part of that vision. A brand purpose unites brand, business and consumer behind a single goal. The purpose of a purpose is to build a connected brand experience.

Or at least, that’s what we’ve been told. People bond to the why, not the what. Customers don’t buy what you do, they buy why you do it. Purpose builds connected brands.

But in the pursuit of that elusive prize – the ‘connected customer experience’ – the product being sold is frequently the first casualty, overlooked in favour of its more glamorous cousin in the next-door-but-one golden circle. Indeed, we might all be wonderful at ‘starting with why’, but it often feels like we don’t even make it to ‘what’ at all. There’s a deliciously hubristic parable in the Fyre Festival story, which took the ‘purpose over product’ approach to an extreme, selling a vision for a product that they hadn’t even invented yet.

Thankfully, Fyre Festivals are not a common occurrence. But misjudged brand purposes certainly are.

The importance of specificity

The loftier and more universal a brand purpose becomes, the less specific, and therefore less distinct the brand idea it directs.

For instance, the Starbucks purpose is to ‘inspire the human spirit’, whilst Coke has a vision to ‘inspire moments of optimism and happiness’. In Singapore, local telco Singtel promises to ‘..make everyday (sic) better’, whilst Barclays Bank has a dream to ‘Help people achieve their ambitions – in the right way’. They’re examples of visions that have become so broad in their pursuit of a universal human truth that they’ve become entirely generic.

There’s a misguided assumption amongst both clients and agencies that a brand purpose is always a social purpose. It’s not. And it’s much harder to carve out a distinctive space when you share your purpose with a hundred other brands united behind the same ‘higher order’ human goal. Brands that sell products to women adopt purposes that help them stand for women. They exhort us to lean in, stand up, stand out, be confident, be real, be yourself, just be. Meanwhile brands that sell products to men tell them to do anything but. It’s becoming harder to tell some brands apart when their signposting is reduced to a naff hashtag and a glossy film that has nothing to do with the product being sold.

Linking brand vision and product truth

Clearly, part of the answer is to avoid having a vague, meaningless purpose. But it’s also about investing in your ‘how’ – the crucial link between the brand vision and product truth.

It’s in this dimension of a brand’s makeup that the inspirational purpose is made tangible. It is here that relationships with audiences are built, and that distinctiveness resides. A brand’s ‘how’ is your brand’s idea.

Nike’s purpose (though they call it a mission) is to bring inspiration and innovation to every athlete in the world. It’s a purpose that’s relevant to their category, specific enough to be tangible, yet broad enough to be inspirational.

It’s how this vision is manifested that really builds a connected experience, however – by motivating and enabling through every touchpoint; from the Nike Run Club app, to She Runs the Night, Nike Coaches, Nike on Demand, right through to specific activations such as the Nike Unlimited Stadium in Manila.

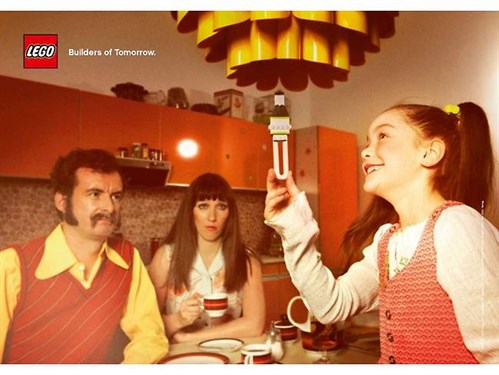

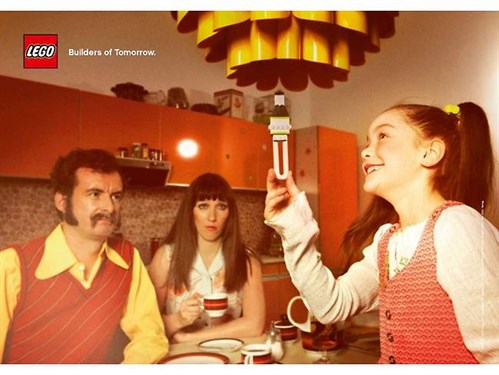

Lego’s brand purpose is to ‘inspire and develop the builders of tomorrow’. Again, it’s a specific and directional statement. But it is how they realise this purpose that defines the brand’s relationship with its consumers and therefore the brand idea: giving users the tools and sparking creativity in play through licensing and partnerships, gaming, theme parks, retail experiences and exhibitions.

Both Nike and Lego offer connected omni-channel experiences that springboard off the ‘how’ to create a bridge between the brand belief and their product.

I’m not sure Nike would be the same relevant, confident and exciting brand if it’s purpose had been something vanilla like ‘Make everyone better’, or whether Lego would still be captivating all of us, regardless of age, if it’s pointed purpose was replaced with a generic vision like ‘inspiring imaginations for a better tomorrow’.

Conversely, it’s also interesting to speculate how much more powerful certain brands could be if they exchanged universality for specificity, and if they focused on the ‘how’ as much as they did the ‘why’.

After all, it ain’t what you do. It’s the way that you do it.

This piece was originally written for the Marketing Society’s Empower magazine.